Post-World War II disillusionment with the machine as an aesthetic value sparked free-form modernism and the interest in organic architecture. More than a theory, organic architecture is a way of life made possible by a unified composition of site, building, furnishings, and surroundings.

The main principles of organic architecture—and of one of its sub-sets known as organic mid-century modern architecture—are building and site, material, shelter, space, proportion and scale, nature, repose. Today—these principles outlined by F.L. Wright and B. Zevi nearly a century ago—are more than ever relevant for contemporary architecture, and at the core of truly sustainable architecture. They stress the necessity for a building to grow out of the landscape, or the urban context, as naturally as trees; the need to use materials minimally, using their inherent texture, color and strength as decoration; the importance of safety and privacy; the notion that nature is the master and from her we derive proportion and scale creating an appropriate setting for human life. An architecture with these qualities—with at its core the user’s spiritual, psychological, and materialistic necessities— is very likely to be loved, withstanding the test of time remaining in use for generations. Therefore, escaping demolition and conserving resources—ultimately becoming the real model for sustainability.

Let’s now turn to the concept of space on which rely all the other principles we just outlined. Space has an elusive and free nature. It can be seen only when confined within the structure of which is the negative image when read in plan or section. Space is truly appreciated through the fourth dimension of time while moving from one point to another. The experience of quality and beautiful space inspires the user and, if only momentarily, lifts humanity out of the dismal grind of existence.

So, when it comes to the creation of space, nature is the master. In fact, it is in her that we observe the principles of harmony and elegant spatial relations. It is in her curves that we find embodied beauty. As A. McRobie points out in his book The Seduction of Curves (Princeton University Press, 2017), “Curves are seductive. These smooth organic lines and surfaces—like those of the human body—appeal to us in an instinctive visceral way that straight lines or the perfect shapes of classic geometry never could.”

These words echo those of Oscar Niemeyer, one of the pioneers of modern architecture. In fact, D. Underwood—in his book Oscar Niemeyer and Brazilian Free-form Modernism (George Braziller, Inc., 1994)—reports that Niemeyer to explain his architecture often said “It is not the right angle that attracts me, nor the straight line, hard and inflexible, created by man. What attracts me is the free and sensual curve—the curve that I find in the mountains of my country, in the sinuous curves of its rivers, in the body of the beloved woman. The entire universe is made of curves—the curved universe of Einstein.”

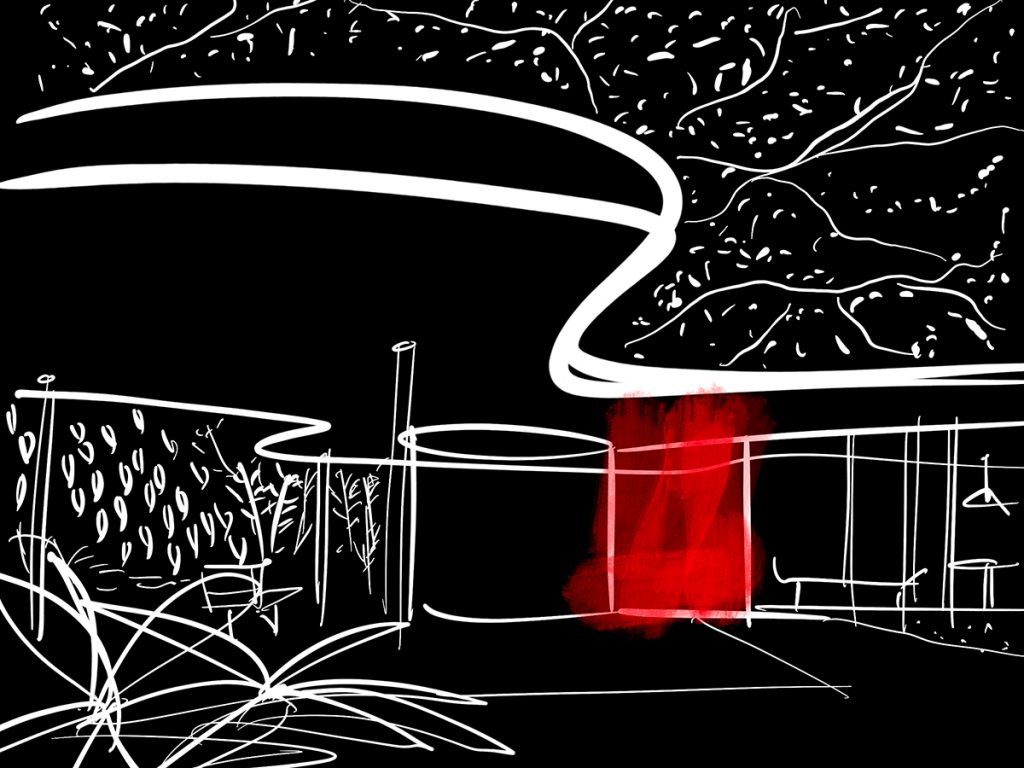

Striving to design in harmony with nature, Niemeyer—in House at Canoas (Casa Das Canoas), Rio de Janeiro, 1953—succeeded in articulating in a cohesive language the principles of organic architecture integrating them with elements of rationalism—reminiscent of the Bauhaus ribbons of glass—when satisfying the function-driven requirements of seamless indoor-outdoor flow as part of the project program.

Describing the project Niemeyer said, “My concern was to project the residence freely and to adapt it to the unevenness of the ground without modification, making it into curves, so the vegetation could enter them without separation.”

House at Canoas embodies contradiction. Through its veins flows the blood of openness and transparency—main floor—reclusiveness and mass on the lower level. But, overall, coherence with organic architecture is very rapidly intercepted. In fact, the sinuous concrete canopy—sheltering the entire main floor—could be a contour of the surrounding orology while the glass walls allow nature to penetrate the volume. On the lower level—where the bedrooms are—the space is perceived as more enclosed contributing to a sense of safety while sleeping, when humans are the most vulnerable. In fact, downstairs bedrooms have only small windows piercing the massive walls. Wilderness is still perceived through them but kept at bay by the mass of the structure. The residence is perceived as a shelter, a safe point of observation from which one contemplates and is enriched by natural beauty. Nature defines the boundaries of the house: jungle on three sides, and—downhill in the distance—the sea with the bay.

This apparently utopian interpretation of domestic architecture is firmly anchored to the ground by a massive native granite boulder that penetrates both levels while leaping outdoors to become an integral part of the pool. The boulder is the pivoting point of the entire spatial composition and a prime example of a Surrealist natural presence. But the main floor—with its fluid space of stone, water, and vegetation—is also a Situationist stage for a domestic Dérive, a framework for life to take place in entire freedom. The horizontal surfaces flow seamlessly indoor-outdoor protected from the harsh sun by the deep overhang of the sinuous concrete canopy. Because of its fluidity, the main floor is in flux and malleable embracing freedom of use and movement, almost morphing into the open public space of a square.

While moving through the residence, episodes of beauty are experienced. Voluptuous sculptures by Alfredo Ceschiatti interact with the sinuosity of the glass walls and landscape—designed by Roberto Burle Marx. A grand piano is surprisingly found outdoors but still protected by the canopy overhang, and the tropical landscape seeping through the glass becomes Niemeyer’s interior designer as pointed out by D. Underwood.

Because of the radicality and clarity of the design, House at Canoas is tangent to R. Venturi’s vision expressed in his book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (MOMA, New York, 1966). As V. Scully elaborates in the book introduction, embracing complexity and contradiction in architecture is rigorously pluralistic and phenomenological in its method. It means to embrace the ambiguity, the surprise. Through movement in space we discover, making going about life bearable.

Ultimately, creation of architectural space is a spiritual act. It embodies poetry and imagination. A way to achieve integration with the universe.